RAKU

“Fixing Light” refers to the activity of the photographer, making permanent the silver salts in on light-sensitive photographic paper. “Fixing Fire” is the activity I engaged in firing raku – making permanent the silver salts in a silica glaze matrix.

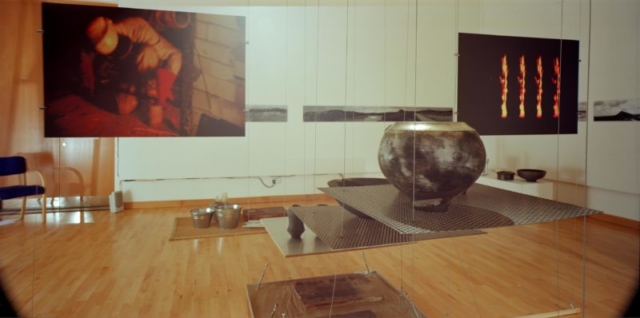

Fixing Light, Fixing Fire was a site-sensitive response in objects, images, and senses to the book I had created with Photographer Rod Dorling and Designer John Bell. It had originated after of an invitation from The Leamington Pumprooms Art Gallery (with support from Arts Council England) to create a touring exhibition. In Raku – Investigations into Fire, which had just been published, we endeavoured to create a document that deals with the interrelationship of ‘languages’: There was the written text that tells a story of raku – an historical process that was revitalised only fifty years previous when the tradition of Japanese Raku was revisited by American potters and re-invented, not just as a means for making objects of contemplation, but as a full-on spectacle fraught with histrionics and excitement. Then there is the ensuing pictorial sub-text that tells a different story – of the ways in which individual potters have re-interpreted that original technique. Lastly there exists the juxtaposition of these two aspects in the overall design of the book. This exhibition aspired to develop that collaboration and to find another reality in the physical existence of this exhibition which furthers that dialogue.

Fire and change are two of the central features of ceramics. To take formless mud, and to fashion it, is a way of creating that allows us to walk in the footsteps of our ancestors; they themselves felt that they were stepping in the tracks of Gods. Ceramic is merely fire-hardened mud – a silty deposit that has been exposed to the heat of a bonfire; and yet these ceramic objects are artefacts that we find long after all other traces of the human beings that made them have disappeared.

Fire plays an ambiguous role in ceramics; it removes clay from the world of mutability and takes it to a new condition of permanence. Fire fixes the manipulated clay, by chemical change, and prevents it from being re-fashioned into a new form. Fire also has a power of transmutation; it can leave an elegant form resoftened and distorted after experiencing the extremes of a prolonged firing, or cracked from a too rapid cooling.

It is not difficult to speculate how our ancestors may have come to imbue ceramic processes with symbolic value. To have observed the shaping of clay into a recognisable form, allowing it to air harden, and then to watch its dissolution into an amorphous state, merely with the addition of water, must have been an early, metaphoric, glimpse of creation, their own final annihilation and yet the possibility for reshaping anew from softened mud. And to arrest that eternal circle by cooking the clay in the heart of a fire might have represented an opportunity to escape that cycle. Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn gives just such a sense of permanence in a fluctuating world.

Potters have the opportunity to engage in this atavistic world every time that they fire a kiln. This alchemical change is an intoxicating fascination involving the exposure of clay objects to extreme experience. The marks left on the clay by the path of the flame tell of some aw(e)ful rite of passage, it is a kind of testing – both of clay and of potter. The raku potter intervenes in this process in the most direct way, by physically removing the red-hot pot, wet with molten glaze, from the kiln, and then reducing it by plunging it into flaming sawdust.

raku seems to be the antithesis of the kind of technological progress and mannered language that is represented by electric kiln firing. It is the unpredictability of intense combustion and drifting kiln vapours that has in recent times seduced so many into trying raku as a way of firing that emphasises accident and chance in the work. These properties of firing owe much to the Zeitgeist of Abstract Expressionism, improvised jazz and a rediscovery of Zen-Buddhist thinking – in all of which ‘Happening’ is an essential part of the process. Now, though, after many years of working with the process the goal is no longer the excitement of seeing what felicitous accidents will happen but establishing ways of firing that will direct the results to a controlled space in which everything that is said is in some way already known.