Durch das Feuer gehen – Trial by Fire

An exhibition by potter, David Jones and designer, John Bell

Keramikmuseum Westerwald, Germany

Catalogue Essay

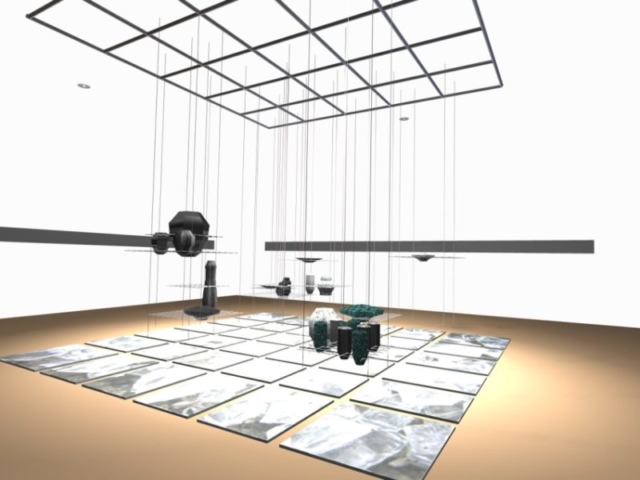

It’s the difference that you notice first, a way of showing that changes your way of seeing – your way of being, even – for this is an exhibition that takes you back to first principles. Everywhere else in this museum (an entire space dedicated to the showing of ceramics – the dream of potters everywhere) pieces are presented in what has long become the accepted vernacular of ceramic display: spot-lights, glass cases, plinths. But in this exhibition the pedestals and vitrines are gone and instead the pots hang suspended, heavy yet strangely aerial, held up, supported – cradled, almost – by industrial steel mesh that is strong yet light, the individual pieces not kept apart in pristine isolation but clustered, huddled together as if for warmth (maternal metaphors come to mind). Conspicuous by their absence, the white plinths (that, in their bare minimality, were trying their hardest to disappear, to shrink from your sights and to focus your wandering eyes exclusively on what’s on show) are, you now realise, anything but neutral. Laden surfaces, rather; sacrificial altars that offer up their contents to view. And, once turned over to your directed gaze, the pieces that are presented to you thus are conceived of in a very particular way: as exquisite, inviting, seductive, feminine, but at the same time as finished, stilled, cold, closed, frozen in time. As objects. As objects, moreover, that inevitably set you up, that invariably position you as the subject, as the solid bourgeois citizen who is possessed of an appraising, appreciative, and, possibly, an acquiring eye.

How break up that sordid contract? How put viewer and viewed into a different relation? How display pots without the deadness of the reliquary? By turning, this exhibition seems to suggest, to theatre. Or rather – since, pooled in their spots of light, the pieces otherwise conventionally displayed could still be thought of as ‘theatrical’ – by turning to dramaturgy, a distinction which exhibition-designer John Bell, with a background in designing for the stage, insists that we make. For it’s not just that the bulbs which illuminate the pieces in this show are never still, the pots constantly moving in and out of the shadows like characters on the stage: we too are drawn in – active participants. Eschewing the balconies and stalls that the museum’s multi-levelled, mezzanined space allows for – vantage points from which you might have viewed the exhibits distantly, as through a proscenium arch – the exhibition-design rather leads you, guides you in. A photographic frieze on the horizon-line – the black-and-white panorama of a Cornish clay-pit – takes you down a ramp, round a corner, so that you are no longer the settled subject, complacently looking on, but now a player, or more, perhaps, a neophyte – like the uncertain initiate whose rite of passage it was once the job of the Greek temple to enact, to dramatise, to event: its mystic architecture leading you up its steps, down shafts, along passage-ways, through labyrinths, confronting you now with dead corners, now with blind walls, until bringing you, disconcerted and blinking, into a bright courtyard lit only by the sky. Revelation.

The very approach to this exhibition is thus experiential, ritualised; and if you’ve come this far you will already encounter the pots in a different way. With their supports gone, their habitual props kicked away, they hover and float, suspended from above, held up from below, their gravity now made visible and their connection with the ground the question that is newly posed. For that is what this exhibition is really about. Clay cut wet from the soil and fashioned into shape…in myth the world over a metaphor for humankind: a scoop of soil, a little spit, the breath of the god infused and lo! a creation. Perhaps every potter lives with that legend, but philosophically-trained David Jones does so quite consciously, his material malleable, mouldable to the fingers, yet with a wayward grain that still resists and insists on going its own way: a whole theology there. So clay has a familiar feel about it, a deep chthonic connection in which we recognise our bodies and ourselves, a creatureliness, a fleshliness. But it possesses at the same time an otherness, an elemental quality that remains alien and strange – the more so, perhaps, for its ancient familiarity. For when you dig down, deep and dark, you don’t know what you are going to drag up, any more than you know what’s at the end of the umbilicus, what prodigy or monster is going to be dragged from the womb. As Freud pointed out in a famous essay, the Heimliche – that which is homely, cosy, warm – also shades off, weirdly, into the Unheimliche, into that which is uncanny and sinister, dangerous because hidden away or secreted from view: something once all too familiar but now frightening and strange because forgotten and repressed long ago.

So the potter’s material (symbolically extracted from the soil) and the potter’s art (his flesh on that flesh, his act of creation, the process by which he brings something to completion, into the light): these will bring with them the shock of discovery, the uncertain experience of finding something which he didn’t know but which, strangely, he finds he already knew. These pots, then – raku-black, austere, matt (against iridescent gleams), their surfaces pitted, and often deliberately cut, gouged, slashed – strain mutely to be understood. But not until the pertinent questioning of an Israeli student would understanding dawn in the maker’s mind and the process finally be complete. Not until then would the connection be made with a darker past; between these blackened pots, bearing the imprint of the potter’s hands, the last thing to touch them before the fire…and other hands, blackened by fire, bodies damaged beyond repair, unceremoniously piled beside murderous ovens, German-Jewish grand-parents, a flight to England, a life of exile, survival, guilt. All known about, and yet not until now known with that uncanny certitude, the unmistakable shock of recognition: the truth embedded in surprise. A finding out which only the act of making made possible, the business of going forward blindly, of not really knowing what your motivation is nor what you are going to unearth. ‘No one kneads us again out of earth and clay’, wrote Paul Celan, his own identity irreparably broken, traumatised by war, ‘no one incants our dust. No one’. Yet this clay speaks, incants on a generation’s behalf – and the more piercingly for not being intentionally or consciously voiced.

This exhibition represents, then, a very personal trial by fire, and one that has a particular resonance – a homeliness, indeed – in finding itself housed here in Germany, a country with which the artist is connected now not only by that past but by experiences that are quite different: a conscious, happy, current present of holidays, of a new German family, of professional connections, of a long career as a successful artist in clay. The enigma of survival. And something literal, perhaps, to be found in the prefix of that word…suggesting that we live on but not only in time – living beyond our predecessors, continuing the family line forward – but also in space: as if to survive were necessarily to live on, that is to say to live on top of or over and above what came before, to tread upon a layer of earth that supervenes between ourselves and history, to walk on the bones of the past. That is our ground. And the pots in this exhibition demonstrate our profound connectedness with it. A geological stratum in which embedded memories – collective as well as personal – are brought up from below, specimens that confront us with the past (archaeology was Freud’s favourite metaphor for psychoanalysis; and the exhibition’s grids and tessellations allude consciously to the techniques used in recording archaeological sites); but a living ground, as well – breathing soil from which that clay is cut and from which those creatural vessels are shaped, speaking to us in a language which we may not be able to recognise at first but which we can still, in this exhibition at least, strive to understand.

Catherine Bates, Professor and Head of English Department at University of Warwick, UK